|

John L's Old Maps / Supplementary Pages: Photos of the

|

|

|

|

THIS IS THE HOWARD CREEK PAGE. |

||

|

This is the fourth in a series of web pages based on visits to Itasca State Park in Minnesota since August, 2009. Rather than inserting revisions and additions to what I had written originally (as I've done with each visit to the common source of the Brule and St. Croix Rivers), these pages progress almost like chapters or blog installments – adding new photos, videos and insights from each succeeding visit and happily not yet laying bare any grievous errors posted earlier. And I'm making plans to go off-trail again to tie together some more loose ends for a fifth page.

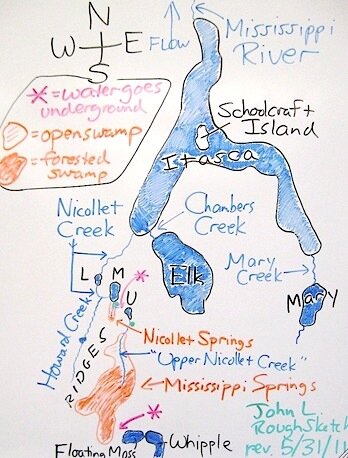

To give some perspective to my very rough sketch map on the right, Whipple Lake is approximately two miles south of Lake Itasca, and the western side of Itasca is approximately three miles from the mouth of Nicollet Creek to the start of the Mississippi. The explorers who wrote about the area took into account the extreme convolutions these streams make as they run their course, so their figures tend to be much higher than what a straight-line measurement on a map would indicate. I do not attempt to be comprehensive in my depiction of important natural features; for example, I only indicate two of the swamps which have been associated with these web pages. The entire area which includes Lake Itasca at its northern extreme and Hernando de Soto Lake near its southern extreme constitutes the real Headwaters of the Mississippi River. Lake Itasca basically serves as a funnel which collects water that flows and seeps from the more southerly lakes, ponds, streams, springs and swamps. Many may "walk across the Mississippi" at the outlet of Lake Itasca, but how many have beheld the very substantial Nicollet Creek which enters into the southwestern end? That is where the fascination begins for, it seems, an ever-dwindling number of students of the nineteenth century explorations by Schoolcraft, Allen, Nicollet, Brower and their associates and followers whose works only begin to be listed here. To reiterate some facts from the previous three pages of this minisite: In the 1830's, the explorer Jean Nicollet considered Whipple Lake as the beginning of the Mississippi River. This lake is fed by springs from the hills, and the outlet flows northward toward Lake Itasca. However, as made known in publications by J. V. Brower (in the 1890s), there is not an open channel over the entire two-mile distance. This is due to a couple places where the water pools up, travels underground and then comes up as springs which re-collect to continue what Nicollet called his "infant Mississippi." These "disconnects" are pointed out on the map with red asterisks, and a video which shows one of them covers the area between the small green dots. What I have labeled as "Upper Nicollet Creek" is not called so officially, and present-day mapmakers conveniently leave it off their charts entirely. Brower found it of enough importance to call it the "Detached Upper Fork of the Mississippi River." Three lakes along the way were noted by Nicollet in his Official Report. As Brower did not think Nicollet had gone all the way to Whipple Lake, he came to his conclusion that the three lakes were those which are labeled U, M and L (for upper, middle and lower) on this map. However, according to the more-recently published Journals, Nicollet most likely had Whipple Lake in mind as his first (upper) lake and "M" (called Nicollet Lake presently) as his third (lower) lake. A summary of his Report and Journals regarding this area is presented here. As for Nicollet's second (middle) lake, I speculate on where that may have been in the discussion below. Also below is a description of my expedition to find Howard Creek whose name was given by Brower in honor of Henry Schoolcraft's daughter, Jane Howard. As noted by Brower (in his 1893 volume referenced here), the head of Howard Creek begins the longest perennial course of open water through the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico, save for the tributaries of the Missouri River. I do not claim that my visit is unique in any way, as – for one thing – the place is probably crawling with deer hunters in the fall. |

The Hike to and from Howard Creek.

Starting from "Upper Nicollet Creek" (UNC) at about the spot where the arrow points to the stream on the map, I headed in a more or less westerly direction, attempting to keep the morning sun on my back as much as possible. (Often my tendency is to drift in a counterclockwise direction and wind up back at my starting point.) A topographical map obtained from Microsoft Research Maps indicated a few ridges to travel up and down on the way to Howard Creek's valley. As I walked from UNC up an incline, the ground appeared quite soggy (Photos 1-2) due to the abundance of springs, and noticeably dry ground finally appeared at the base of the first hill (Photo 3). As I meandered toward the Howard Creek valley – maneuvering around fallen trees and thick brush – things got a bit greener (Photos 4-5), and the ground felt soggy again, even at the top of a hill. My first, somewhat distant glimpse of Howard Creek was a small pond (Photo 6) which I surmised may have been backed up by a beaver dam. Indeed, a lodge is seen in this photo taken with my cell phone from a different angle. Walking in a southerly direction (i.e., upstream), I found the creek running clear over rocks and sand (Photo 7) and coming out of a multi-tier beaver dam which resembled a series of locks. Above the top dam (Photo 9) was a rather large pond (here and also Photo 10) containing at least one beaver lodge. A greenish-gray, cloudy appearance was seen in the pond and also at an intermediate level between dams (Photo 8) – probably indicating (by refraction in the shallow water) a muddy substratum. Brower described Howard Creek in his 1904 volume as a "small picturesque little stream with several miniature waterfalls." In place of waterfalls, I saw these beaver dams! The activity of these animals was quite evident (Photo 11). Heading farther upstream, I noticed small spring-fed streams pouring into the pond (Photo 12), and one in particular (Photo 13) was seen to trickle out of an opening in the hillside.

Even though I was repeatedly giving myself a sponge-bath with insect repellant, they got to me anyway, drilling right through my jacket (Photo 14). As much as they liked having me around, I felt a need to bid them and the Howard Creek valley adieu, although an affectionate cluster of marsh marigolds (Photo 15) did its best to delay my departure. Heading back in a roundabout fashion, I came to a "bay" on the western edge of the swamp which encloses the Mississippi Springs (Photo 16). Back to the hills for easier walking, I saw an incredible number of downed trees such as one that lay on the ground over its entire length of well over 100 feet (Photo 17), winding its way through the vegetation like a huge above-ground pipeline. It must have made an incredible noise when it fell. Recycling of the elements was evident as fungi (Photo 18) and undoubtedly bacteria were busy at biodegradation, ultimately releasing nutrients for the sustained continuation of life in this self-perpetuating forest. Revisiting "Upper Nicollet Creek" (UNC) and Clarke and Brower's Theoretical Lakes of Nicollet.As the "Upper Nicollet Creek" rushes away from the Mississippi Springs toward what Brower called the "Upper Lake" of Nicollet (which, as we recall, really wasn't), it passes through a non-forested swamp (Photo 19) southwest of the "Nicollet Cabin," an interesting structure situated just off the Nicollet Trail. That this swamp may have been inundated significantly in years past was evidenced by the presence of old beaver dams (Photo 20). A functioning beaver dam at the downstream edge of the swamp could raise the water level considerably, forming a good-sized pond which may have been the middle (second) lake which Nicollet saw as he made his way north from Whipple Lake to Itasca. A short distance upstream, an iron spring with an oily sheen (Photo 21) trickles into the creek. Downstream – approaching Brower's "Upper Lake" – an old course of UNC is evident among the remains of beaver dams from many years past (Photo 22 and also here). On the west bank of the lake (more like a pond, actually), a large, old red pine which I had seen on my first visit to this area (here, Photo 5) was sadly rendered horizontal (Photo 23). This pond where UNC backs up is enclosed in an oblong depression, and the ridge in the northwest corner which prevents a surface outlet leading to the Gulf of Mexico can be seen in Photo 24. In light of my several visits to this area over the past two years, I altered the whiteboard map above to accomodate Clark and Brower's original observations of the relevant streams and lakes with their designations in green lettering. Naturally this will make sense only to those with these references in hand. Click here – and also here for a close-up. (Left out of the legend, no. "2" of Clarke was later named Nicollet Springs.) What Clarke (prior to Brower) had thought was the "Upper Lake" of Nicollet (shown in a relatively dry state here, Photo 9) was considerably flooded during the present visit (Photo 25). It isn't hard to imagine a past connection with the nearby Nicollet Lake; the only thing presently in the way is the Nicollet Trail which runs atop what appears to be an artificial elevation. On Clarke's survey map, he placed lakes (or ponds) "F" and "G" close together. "G" is Floating Moss Lake, an originating source of water for the Mississippi Springs which feed the UNC according to Clarke, Brower, and subsequent observations. Later, after making his way upstream what has since become known as Howard Creek, Clarke considered the originating source of water in the springs which feed the creek as the same "F." This would appear to be highly unlikely, and such closeness of the sources of Howard Creek and the UNC is not seen in Brower's maps; furthermore, the land is definitely elevated in between. Whatever Clarke may have meant by an "F" in any case, I have indicated as such on my sketch map. I did notice at least one water-filled depression in the hills to the east of Howard Creek which I could have also marked as an alternative "F". A PowerPoint presentation of all this may be in order someday, although I am afraid that those really interested in such detail have long since passed on.

Winding Down this Visit.What I initially thought was a wild strawberry flower is probably something very similar. Usually this plant has flowers with five petals in a cup-like arrangement, but I have frequently seen flattened-out 6 and 7-petaled variants (here and also Photo 26). On the way back home on May 26, my trusty vehicle – the 2001 Mitsubishi-built Dodge Stratus Coupe (Photo 27) – hit the magic 345,678 milestone (Photo 28). Finally, it is broken in and good to go for many more visits to historical sites, the likes of which one does not learn about from our state and federal tax-supported institutions but must go off-trail to see and touch first-hand. Microbiology.

"Total" aerobic plate counts of water samples with the use of Plate Count Agar (PCA) often yield interesting colonies of chemoheterophic bacteria in substantial numbers, but I was not expecting to find a colony of the green alga Chlorella along with the bacterial colonies on a plate of PCA inoculated with 0.2 ml of Upper Nicollet Creek water. This was purely "accidental" as I am sure this is not an approved method for isolating Chlorella. (No special provision of light was made for the incubation of these plates which was done at room temperature with minimal ambient light.) A microscopic view of cells from the colony is shown here and a subsequent streak plate is seen here. A Google search revealed that simple heterotrophic cultivation of Chlorella has been practiced for decades, so its growth on PCA is apparently no big deal after all. This culture also grows well on Heart Infusion Agar and Nutrient Agar, and I am now maintaining it on slants of the latter medium. |

|

E-mail me at: |

Unless otherwise noted, all photos herein are by |

Click here for a brief video of my Howard Creek Expedition

Click here for a brief video of my Howard Creek Expedition