|

John L's Old Maps / Supplementary Pages: Photos of the

|

|

||

|

|||

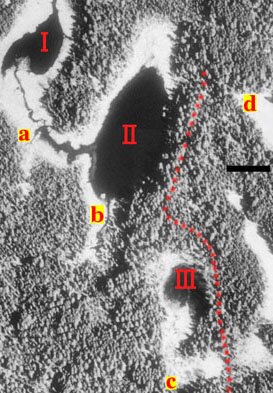

After reading many of the histories of exploration concerning the source of the Mississippi River and the ultimate sources of Lake Itasca from which the river flows, I felt the need to make a rush trip to the area in late August, 2009 to (at least) check out the three main feeders of Lake Itasca – i.e., the creeks named for explorers Jean-Nicolas Nicollet and Julius Chambers, and pioneer Mary Turnbull. THE NICOLLET CREEK SYSTEM Nicollet Creek is the major inlet, emptying into the southern end of the Southwest Arm of the lake. The aerial photo on the right shows the three lakes determined in the 1893 publication by J. V. Brower (the original Commissioner of the Itasca State Park) to be those that the explorer Nicollet noted in his report to the government which was published posthumously in 1845 and based on his 1836 explorations of the area. The lakes are designated here by Roman numerals as follows:

Howard Creek enters Nicollet Creek at a, and Brower mentioned the origin of this stream (in the hills a mile to the south) as the farthest reaching of all when it comes to determining the total distance of open water to the mouth of the Mississippi (apart from streams of the Missouri River system, one must add – at least parenthetically). The dotted red line represents a segment of the well-maintained Nicollet Trail. Among many other natural features, it passes by the Middle Lake (II, marked "Nicollet Lake" at the park) and also a swamp (d). The swamp was one of two possibilities thought by Hopewell Clarke (in 1886, previous to Brower) to represent Nicollet's upper lake – his alternative being what is called "Nicollet's Springs" on the park's trail map (and marked b on the aerial photo). With the discovery (in 1921) and study of Nicollet's personal journals (which I just found for myself in mid-October, 2009), some clarity may be obtained from his descriptions of the natural features. In fact, Martha Coleman Bray – the editor of his journals (published in 1970) – designated Whipple Lake (about a mile south of III) as his upper lake and then Nicollet Lake (II) as his lower lake. Regarding the entire stream from his upper lake in the journal entry for his August 29, 1836 visit, Nicollet refers to it as "the Mississippi" and does not note anything about any discontinuity of open water such as what is indicated above regarding underground seepage from III into II. His final sentence for August 29: "As the Mississippi issues from this lake [his lower lake], it resumes its meandering across more marshes and two or three miles later enters Lake La Biche [Itasca], heads north, veers south and descends toward the Gulf of Mexico." One may not necessarily expect that open and continuous streams in the days of Nicollet (or even Brower) are still so. On a future visit to Itasca Park when I can head off-trail and into the woods (which is where I generally belong anyway), I would like to see for myself if I can trace the stream (c) shown in Photo 1 and the video up to Whipple Lake – and also check out the area between III and II. For convenience on this web page, I will herein stick with the designations of the lakes (Upper, Middle and Lower) by Brower which are given above with the aerial photo – keeping in mind that Nicollet actually may not have thought about them that way.

FIELD TRIP!! While going off-trail to get a photo of the Upper Lake (from its southern end near c), the sound of running water was quite evident and easily led me to the above-mentioned "detached upper fork" of Nicollet Creek (of which I did not fully realize the significance at the time). This stream and the associated beaver dam and a somewhat distant view from the south of the swampy (boggy?) Upper Lake are the subjects of Photos 1-3. A movie of the general area can be seen by clicking on no. 4. An old red pine which has seen better days (Photo 5) was visible on the west side of the Upper Lake. Flowers in the area were hosts to numerous bees (Photo 6), and a dense forest of fungi was evident upon some of the fallen trees (Photo 7). Photos 8 and 9 are (respectively) of the Middle Lake ("Nicollet Lake") and the nearby swamp labeled d above. I could see the possibility of a past connection between the two; this was shown by a ravine which, however, was interrupted by the elevated trail. At any rate, the sight (from a high point near the trail) of the Middle Lake and the valley beyond is truly impressive. A typical view of the Nicollet Trail is seen in Photo 10. When getting back to where I had "illegally" parked my car on the Wilderness Drive, I was happy to see it still tucked off to the side of the road. Note in Photo 11 how the officially designated 4-space parking lot for the Nicollet Trail can easily be filled by one car-trailer combo (the color of which is changed to maintain anonymity). Nearby, Nicollet Creek crosses under the road on its way to Lake Itasca; views looking upstream (toward the Lower Lake) and downstream are shown in Photos 12 and 13, respectively. Photos 14-16: A short distance to the east of the Nicollet Trail parking lot, one can view the expansive Elk Lake which empties via Chambers Creek into the Southwest Arm of Lake Itasca which is shown in the background in Photo 16. Julius Chambers was a notable 19th-century explorer of the area and is credited with the discovery of Elk Lake, but he receives minimal attention in the park's historical presentations. This fact is almost as regrettable as the general non-mention of Lt. James Allen who was the topographer, head of the military escort, and author of the official government report of the Schoolcraft-Allen Expedition of 1832 whose main intent – as ordered by the War Department – was to visit and vaccinate the Indians of the northwestern Michigan Territory. Other participants involved in this effort were Dr. Douglass Houghton and Rev. William T. Boutwell. With the guidance of the natives, the expedition managed to visit the source lake for the Mississippi River (Lac La Biche, renamed Lake Itasca by Schoolcraft) and finally fix its geographic position and also that of the northward flow of the river out of the lake. (Note the references here.) Allen happened to get a small lake named for him at the park, but it is one which he would not have seen, as his travels with Schoolcraft did not take him that far south. For awhile, Elk Lake was given the name Lake Glazier by Willard Glazier, the only one of the historical figures to name something in the area after himself. However, Glazier's various misrepresentations concerning the ultimate source of the Mississippi above Lake Itasca (noted in the references here – especially in Clarke and Brower) were discredited by reliable investigators in the late 19th century, and the name Lake Glazier was stricken from school textbooks by State law as a result. Glazier is given some prominence at the park's visitor center, but happily it is pointed out that his published plagiarisms and falsehoods are what sparked the thorough on-site investigations in the late 19th century which led to Brower's official publications on the subject. Photos 17-18: The other notable inlet to Lake Itasca (this one into the East Arm of Lake Itasca) is Mary Creek which runs through the beautiful Mary Lake, shown here in the early evening of a generally rainy day. As for the open water sources of the Mississippi River (as opposed to swampy terrain and underground seepage), the originating streams of Mary Lake almost reach the latitude of those in the Nicollet Creek system. Photos 19-21 were taken while traveling along the eastern to northeastern side of Lake Itasca. In Photo 20 can be seen Schoolcraft Island (the dark thicket of trees near the center) and a view through the length of the Southwest Arm in the far distance. And no visit to the park is complete without a walk across the river (Photo 22) where it runs out of Lake Itasca. Personally, I will always intend on touching base with Nicollet Creek (his "Infant Mississippi") for future visits. Photo 23 looks downstream from a footbridge close by. A little farther downstream, the Mississippi rushes through its first (and only?) culvert and into a marsh (Photos 24-26, taken while briefly passing through the area in late March, 2010). Near the outlet of the lake is a historical plaque associating the course of the Mississippi with definition of the boundary of the old Northwest Territory (Photo 27) and also an outdoor amphitheatre (Photo 28) which is just the thing for presenting lectures on history – natural and otherwise. I should mention that the historical presentations at various locations in the park provided an abundance of interesting information about the native population, the early settlers and the various conservation efforts over the years. Attempting to catch up on these things as well as tracing some more streams will certainly take up several more visits. PREQUEL On the day before my first Itasca park field trip, the very first thing I did when I got to Bemidji (my "expedition headquarters" at a local motel) was to go north of town to locate Lake Julia – named in 1823 for a deceased sweetheart by the Italian explorer Giacomo Constantino Beltrami whose portrait is shown here. Beltrami determined the lake to be on the high ground between the Mississippi River and Red River drainage areas (to the south and north, respectively) with its waters seeping into both watersheds. Evident these days is a stream from the lake that flows northward. Lake Julia is shown in Photo 29, and a plaque commemorating Beltrami is seen in Photo 30. |

|

Continued on |

The aerial photo is a composite of images from |